Protecting child translators: no easy solution

How translators can help protect children’s rights, build trust and inclusion

A few months ago, I saw a post by Bill Rivers about an award-winning short documentary film called “Translators: the untold story of children who give a voice to a generation.” The documentary left me asking, what can we do better to protect the rights of child translators?

It’s a touching film, pointing out that 11 million children in the United States alone act as translators and interpreters for their families. They are sometimes the only family member who speaks English, putting a huge burden on them, and a responsibility that they should not have to bear. The children are aware of the responsibility; one child is terrified of making a mistake when interpreting for doctors talking about her sister’s surgery. At the same time, they are proud that they learned English and can help their parents and siblings; their parents gave up so much so that they, their children, could have a better life.

Of course, this is an issue everywhere when people move, or are forced to move, to another community. Children often learn the local language more quickly and are relied on to translate or interpret for their family.

Sometimes, there are no other options. Professional translators and interpreters may not be available. And sometimes, parents prefer their children to interpret because they trust them.

Too often, though, bilingual children are just convenient. Service providers haven’t invested in or don’t have the budget for professional translation and interpretation, even when there is every indication that it is needed. Children are put in difficult positions, asked to do things that no child should ever be requested to do, and they can suffer as a result.

Children have special rights and should be protected at all times; often we fail to recognize these rights. CLEAR Global/Translators without Borders and others have researched cases of children who translate and interpret. By employing research, professional language services, and accessible, multilingual resources, we can protect children’s rights and ensure people get the information they need. On International Translation Day, a day when we celebrate translators, we want to highlight the critical role translators can play in protecting children.

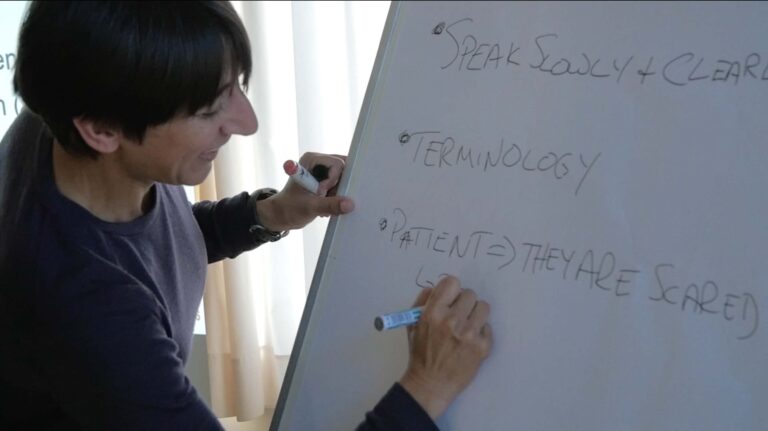

Know what language capacity you need

During the European refugee response, professional interpreters were rarely available so children frequently acted as interpreters for family members and peers. Our research found that a 13-year-old Afghan boy had been asked to interpret on his first day at state school in Greece. Children also shared that they had to act as interpreters during health care visits, because medical staff mainly spoke Greek and English. For these children, finding the right words or specialized terminology needed to talk about medical issues, be heard, and get help, was difficult. And, as in the film, they were terrified that they’d make a mistake and put their family member’s life at risk.

Service providers should find out what languages people speak and use that data to articulate the need for language professionals. Collect language data to understand your community’s most needed language pairs and use that data to advocate to donors, local government, and policy makers on the need for language services. Work with professional language service providers to ensure that the most vulnerable people have access to the information they need.

Translators and interpreters – not just nice to have

An interpreter’s role is usually to be neutral and independent, children acting as interpreters (so-called ‘language brokers’) do it to support their family. Negative feelings towards having to act as a child ‘language broker’ have been associated with depressive symptoms and increased risk of behaviors such as marijuana and alcohol use among children in the USA.

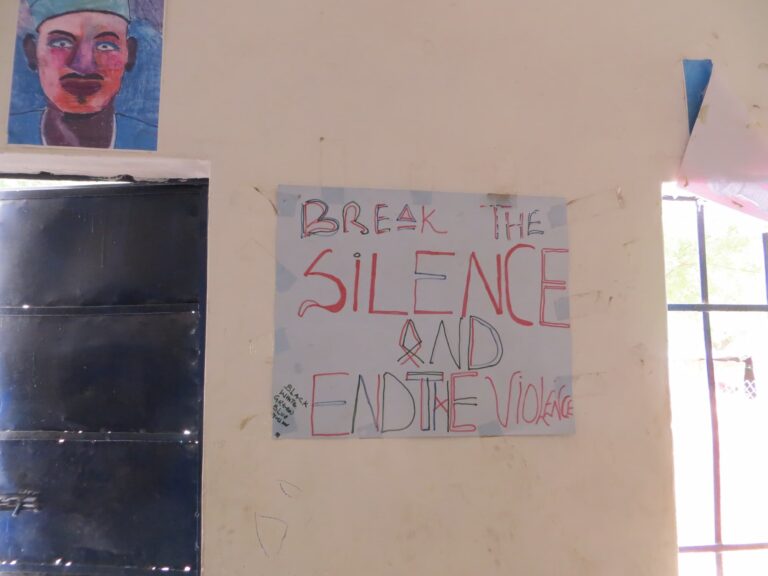

Interpreting can create a stressful or exploitative environment, especially for children who already face other vulnerability concerns. A community social worker in Rome shared an example of a teenage boy who had to interpret for his Bangla-speaking mother at a police station, where he had to explain how his own father had sexually assaulted his mother. Appropriate resourcing for paid, trained, adult interpreters is needed.

All donors should insist on providing resources for language professionals to support service provision. This protects children from difficult, stressful situations and upholds their right to be children.

Tell people about language resources available to them

All the research emphasizes that the impacts for children and young people can be complex. Alongside the undue burden, a range of positive effects are noted. In the UK, when migrant children acted as interpreters, their parents felt less stress and frustration about the resettlement process, which led to more effective family functioning. Helping their parents solve problems meant that children developed ways to protect their families’ dignity in situations that could have become discriminatory or humiliating. Many child interpreters ultimately viewed this task as a ‘source of pride.’

Parents often feel the burden they place on their children too; they are proud of their children and want to protect them, but don’t know what resources are available.

Service providers should raise awareness of available resources and promote the use of translators and interpreters when the support is available.

Make content simple and easy to understand.

In some of the communities hardest-hit by flooding in Pakistan in 2022, research on the reach of flood-related information found that children were relied on to relay information to their parents. With literacy levels very low, children were often the only family members who had been able to go to school. Some women suggested that organizations develop written materials about what to do during floods with school children in mind as the main audience. “The message should be something that our children can read easily and explain to us,” noted one female domestic worker aged 36-55, Kaachi Abaadi, Rajanpur District, Punjab.

When children are the only option, make content as simple and accessible as possible, using plain language principles and ensuring the content is age-appropriate.

Children are … children

Children are often asked to interpret sensitive, complex or distressing topics that can have deep impacts on their well-being. For example, a child interpreting for her mother reporting domestic violence to the police. Or this five-year-old Afghan refugee to the UK. In immigration interviews, she had to explain the violence and trauma her family had experienced in Afghanistan and at the hands of people smugglers. Even for trained professional interpreters, this can lead to vicarious trauma; children should not be expected to re-live or interpret traumatic events.

Never rely on a child to interpret something distressing or traumatizing. Find professional interpreters and translators to protect children from undue stress and trauma.

What’s next?

Children have specific rights under the Convention on the Rights of the Child. These rights should be upheld at all times. Too often, their rights are not upheld because we fail to provide interpreters and translators.

All people have a right to information in their language. Language access is a right for everyone.

Professional interpreters and translators are critical to ensuring that children are protected and that people get information they can understand. All service providers should include provision for professional language services in their budgets.

Upholding these rights is fundamental to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). With a commitment to ensuring no one is left behind, including marginalized groups, and combating inequalities, the cross-cutting issue of language inclusion should be key. Yet there is a lack of language awareness in the articulation of the SDGs.

Over the next few months, CLEAR Global/Translators without Borders will be talking more about how language access, particularly through translation, interpretation, and the development of language technology can help ensure that the SDGs become a reality for everyone. Including, and especially, children.

About the author

Aimee Ansari was appointed CLEAR Global’s (then Translators without Borders) first Executive Director in 2016. The organization had a team of three full-time staff members at the time. Seven years later, CLEAR Global has grown and expanded our work beyond what she (or the Board) thought possible. A natural “disrupter,” Aimee saw the potential use cases for CLEAR Global’s innovations, hired an excellent team and put new thinking to work for the most marginalized. Aimee has over 30 years of experience in leadership positions in large humanitarian and development organizations. She led UN programs in Kyrgyzstan, Yemen, and Bangladesh, and worked in humanitarian crises from the Tajik civil war to the earthquake in Haiti, the conflicts in the Balkans to the Syrian refugee crisis and the conflict in South Sudan. Aimee has worked with Care, Oxfam, Save the Children and the United Nations.