"It takes days for alerts to come": Indigenous participation in early warning systems in Bolivia

Indigenous communities in Bolivia want access to practical, actionable and timely early warning systems in a language that they can understand.

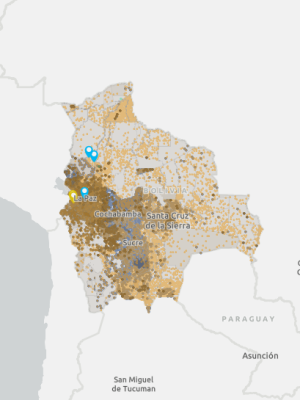

They are increasingly exposed to a range of climate change-related threats that are reshaping their cultural and spiritual landscapes. In northern Bolivia, the Tacana face wildfires, floods, and droughts, driven by a combination of deforestation, climate change, and extractive industry activities. In the south, Aymara communities suffer from prolonged droughts, hailstorms, heavy rainfall, and frost, threatening their traditional ways of life. These environmental shocks have disrupted local ecosystems and livelihoods.

Between March and April 2025, CLEAR Global, in collaboration with Practical Action and the University of Edinburgh and funded by the Lloyd’s Register Foundation, engaged with four Aymara- and Tacana-speaking communities in the La Paz department to better understand their communication preferences for early warning systems (EWS) aimed at predicting and mitigating disasters such as floods, droughts, and wildfires.

Here’s what community members had to say about current early warning systems that are meant to protect them:

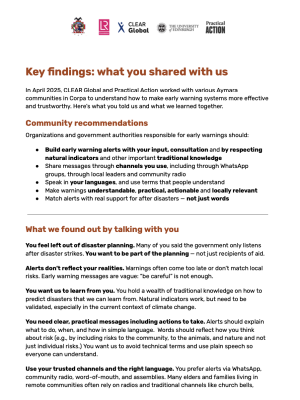

Existing official early warning systems and government alerts are often ineffective. They are not timely, practical, or relevant to the specific needs and risks faced by Aymara and Tacana communities. Many people report not receiving any information at all, and when alerts do arrive, they use terminology that doesn’t match local realities.

There is a critical demand for warnings to be delivered in local Indigenous languages, specifically Aymara and Tacana, and to incorporate Indigenous knowledge about weather patterns and natural indicators alongside scientific information.

Indigenous languages are intrinsically linked to the preservation and transmission of traditional knowledge. This includes the understanding and interpretation of natural indicators used for weather and disaster prediction. The potential loss of these languages is seen as a vulnerability, directly impacting the ability to pass down vital knowledge needed for disaster preparedness.

Communication methods must account for varying language proficiency and literacy levels, particularly relying on oral communication. Many community members, especially older women, have low literacy rates or understand spoken language but cannot read it. Oral tradition is a strong way knowledge has been passed down, making spoken messages via channels like radio vital.

Indigenous communities feel excluded from government disaster planning and response. This leads to a sense of being forgotten and a reliance on their own internal resilience, leadership, and traditional practices.

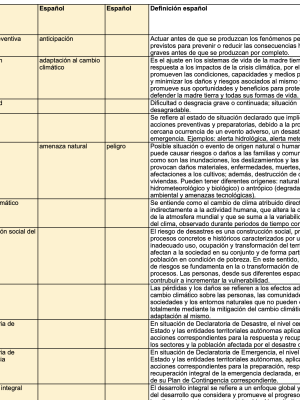

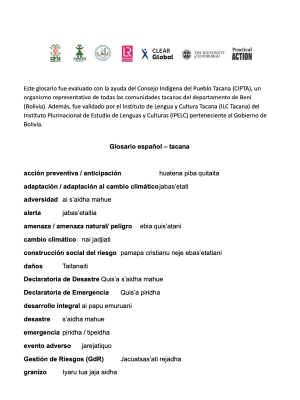

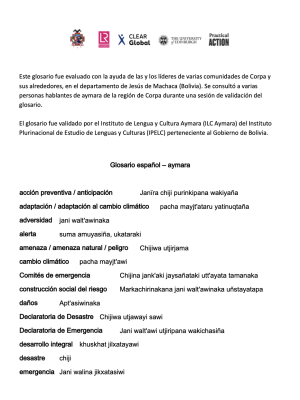

Official disaster risk terminology is often confusing and lacks local relevance. Technical terms like “resilience” or “recovery” do not translate directly or resonate culturally and emotionally with community members. This requires moving beyond literal translation or borrowed concepts.

Communities desire training in modern disaster preparedness and response. They are open to integrating new tools and knowledge with traditional practices, such as using mobile applications for weather forecasts. They also emphasize the need for long-term support beyond warnings, including help with land rights, sustainable livelihoods, essential communication infrastructure and addressing the root causes of vulnerability.

All materials are also available in Spanish.

Find out more about Practical Action’s work in Bolivia.